Word: Ayu Arman

TANAH MERAH, THE EXILE LAND OF BOVEN DIGOEL

In the end, my feet touched down in Tanah Merah, Boven Digoel – South Papua. Susi Air’s plane flew me from Mopah Merauke Airport to Tanah Merah Airport, the capital of Boven Digoel Regency located in the southern part of Papua.

“Boven” in Dutch means “upper” or “above.” During the Dutch East Indies era, Boven Digoel Regency was known as “Digul Atas,” which translates to “Upper Digul.” Before I set foot in Tanah Merah, the name Boven Digoel was not unfamiliar to me. I knew this region from history books, which mentioned it as a place of exile for Indonesian independence fighters and considered it dangerous even to this day because it is difficult to access from the outside world.

Kamp Digoel is located in the heart of the Papua wilderness. There are three ways in today’s time to reach Digoel from Merauke. First, by plane, but flights from Merauke are somewhat infrequent. This is the fastest way but quite expensive. I am grateful that I was able to fly to Boven Digoel with a Susi Air plane piloted by Captain Russel Whitebeard and Co-Pilot Andrey.

At that time, the road from Merauke to Boven Digoel couldn’t be traversed because half of the Merauke – Digoel route was still unpaved, and it was the rainy season, making the roads impassable. Coincidentally, Susi Air’s plane was chartered by the Boven Digoel Regency Government to transport a deceased person from Tanah Merah. So, I, who was working with the Boven Digoel Regency Government at the time, could hitch a ride on this Susi Air plane. I was surprised to learn the cost of chartering the plane – it was 50 million for one trip. So, I express my gratitude to the universe and the land of Papua for making it easier for me to set foot in Digoel.

I was with Captain and Co-Captain of Susi Air.

Secondly, the journey to Boven Digoel can be done by an old ship, and the journey can take up to a week if the water levels are not low.

Thirdly, you can travel by land using a highline. The fare is Rp 700,000 per person. If it’s dry season, the overland journey takes around 11 hours from Merauke.

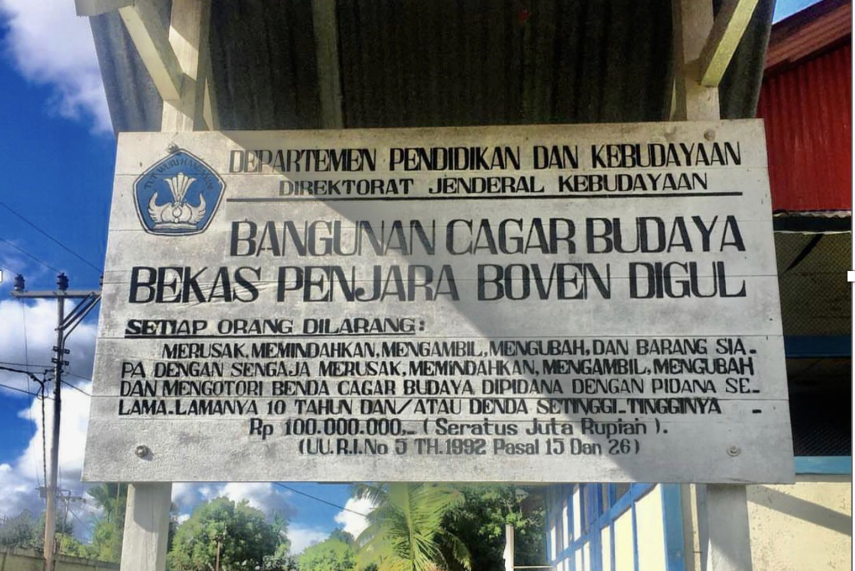

PRISON SITE IN TANAH MERAH

When you disembark from Tanah Merah Airport, you will immediately see the Bung Hatta monument at the intersection of the road, across from the Boven Digoel Police Resort Office, which was built in 2004. The statue of Mohammad Hatta, the Proclaimer, is a symbol that Boven Digoel was once an important place in the history of Indonesia’s independence movement.

The statue of Bung Hatta stands tall as you enter the capital of Tanah Merah-Boven Digoel.

As recounted in the history books, in 1907, as part of their military exploration to assert Dutch authority in Papua, Dutch soldiers navigated 540 kilometers up the Digul River, cutting through the Boven Digoel Regency. At that time, Tanah Merah was still a remote area inhabited by primitive indigenous tribes, plagued by a high malaria rate, and surrounded by swamps inhabited by ferocious crocodiles. This was one of the reasons why the Dutch government established an exile camp in this location. Escape would not be easy for the prisoners as the surrounding area was still dense wilderness, with rivers and swamps teeming with crocodiles.

Before Dutch exploration, Boven Digoel was already known to the Merauke community, especially the Chinese ethnic group, for its brilliant plumage Birds of Paradise, which were hunted for adorning women’s hats. In 1926-1927, there was a major communist uprising against the Dutch government in Banten and West Sumatra. Captain L. Th. Becking managed to quell the rebellion and was ordered to establish an internment camp in Tanah Merah, Boven Digoel, on January 26, 1927, along with 120 soldiers, 60 laborers, and the first group of 1,300 prisoners.

Several Indonesian independence fighters were also detained in Boven Digoel. They included figures like Bung Hatta, Chalid Salim, Sutan Sjahrir, and Bondan, who arrived on February 22, 1935, before being transferred to Banda Naira on January 30, 1936. Additionally, there were several other fighters such as Aliarcham, Sardjono, Mohammad Sanoesi, Soenario, Soemantri, Dachlan, and Najoan. The highest number of detainees in Boven Digoel was in 1929 when the camp held 2,100 people (comprising 1,170 men, 400 women, and 500 children). Approximately 1,500 people had been released within a span of about ten years.

Bung Hatta and Sutan Sjahrir only briefly stayed in Tanah Merah before being transferred to the Tanah Tinggi prison for approximately a year, and they were among the 1,500 people who were eventually released. Tanah Tinggi, located about a 3-hour river journey from Tanah Merah, was a special prison for those who rebelled against the Dutch government in Tanah Merah.

Bung Hatta’s chair in the Tanah Tinggi prison.

Once again, I am grateful to be able to visit and witness firsthand the sites where the heroes of this nation were imprisoned. In Boven Digoel, there are actually three prison sites: Tanah Merah prison, Gudang Arang prison, which has been completely eroded by the river, and Tanah Tinggi prison, which now remains only as rubble and a plaque.

The Tanah Merah prison complex consists of three main buildings: a barracks that could accommodate around 30 detainees, a room for storing the prisoners’ eating utensils, and a bench where Bung Hatta would often sit and read books. There are also three small detainment rooms. These buildings are located to the left of the main gate. In the central area, there is water storage, a kitchen, and a bathroom. To the right of the gate, there are four detention rooms measuring 2 x 2 meters each, one barracks measuring 4 x 5 meters, and a toilet facility.

Currently, this prison site has drawn the attention of the local government and is maintained by the Boven Digoel Police Resort because it is also used by the police to discipline members who violate regulations. Behind the prison building, there are two large buildings measuring 50 x 15 meters each, which are currently used as police dormitories for the Boven Digoel Police Resort. On the side of the Boven Digoel prison site, there are two other buildings.

One of these buildings, which was formerly used as the Dutch police guard office, is now used as the office of the Boven Digoel Police Resort, while the other building serves as the residence of the Boven Digoel Police Chief. Several other Dutch-era buildings are also used as a post office, a Mandobo sub-district police office, and residences for the people living around the Boven Digoel prison site. Approximately 1.5 kilometers from the Tanah Merah prison site, in Kampung Wet precisely, there is the Tanah Merah Heroes Cemetery Park. In this cemetery park, there are 42 graves of heroes who passed away in Boven Digoel, as well as the graves of several traditional and community figures from Boven Digoel.

The Tanah Merah prison site in Boven Digoel is now quite well-known among both domestic and international tourists, especially among the families of those who were once exiled to Boven Digoel or the families of Dutch military officials who wish to visit the area where their relatives once lived.

Get to know the Korowai Boven Digoel Customs

In addition to visiting the prison site, I had the opportunity to visit the village of the Korowai tribe deep in the forest. The natural conditions in Tanah Merah consist of lowlands and swamps, as well as two major rivers, the Digul River and the Kou River, along with their tributaries, which are the lifeblood of the people living along their banks. Furthermore, the dense lowland forest also significantly influences the social life of the people in Boven Digoel. The residents of Boven Digoel mostly live around the rivers and forests, so the patterns of community life among different tribes are quite similar, although some striking differences can also be found, such as the treehouses of the Korowai tribe. This tribe was only discovered about 30 years ago, and at that time, they still lived in treehouses, which is why they are often referred to as the “treehouse tribe.”

The name “Korowai” was first introduced by a Dutch linguist and missionary named Father Petrus Drabbe, which was published in the Oceania journal in 1974. Before becoming an official name, the term Korowai was often interpreted as “living” or “people who live” and carried the meaning of the distinction between living people and spirits.

The local government of Boven Digoel pays close attention to the development of this tribe, especially because they are relatively less developed compared to other tribes. Of the 20 districts in the Boven Digoel Regency, the Korowai Batu people generally live in districts with lowland topography, such as the Yaniruma district.

Almost all Korowai tribes live in treehouses, hence the nickname “Treehouse People.” These treehouses are about 15 meters high and are constructed without using a single nail; instead, they use ropes made from Gnom trees. The roofs are made from sago leaves, while the walls and floors are made from the bark of Damar batu trees. Additionally, the stairs are carved from a single tree trunk with footholds attached for climbing.

The treehouses have a partition that divides the space into two rooms, one for men and one for women. Each room has a fireplace, and there is a small door that connects the two rooms. In the past, during the night, the ladder leading to the house would be lifted to prevent enemies or wild animals from climbing up.

Today, most Korowai settlements in the Boven Digoel Regency are no longer treehouses. Treehouses are still constructed as a part of cultural preservation and as a marker that the Korowai people inhabit the area. For example, in the city center of Tanah Merah, there are treehouses, but the owners live in houses on the ground. Korowai tribe villages in the Boven Digoel Regency are now located along the Danowage Village and Waena Village route in the Yaniruma District, among other places.