Word: Ayu Arman

My feet, heart, and mind have once again found their grounding on the land of Oksibil Valley, in the Star Mountains, a valley located in the eastern part of the Central Mountains in Papua. These mountains constitute the highest range of fold and thrust mountains in Indonesia.

Oksibil Valley is encircled by four towering peaks: Mount Juliana, also known as Puncak Mandala (4,700 m), Mount Goliath, or Puncak Yamin (4,595 m), Mount Antares (4,170 m), and Mount David (4,581 m). Among these mountain summits, Puncak Juliana is the highest, covered in snow, and it extends to form a cluster of stars. It is this resemblance that gave rise to the name Star Mountains.”

Their ancestors referred to the highest mountain as Mount Aplim-Apom, the highest land of their origins created by Atangki (the Creator). They called it the Aplim-Apom people.

Several major tribes inhabit the Star Mountains, namely the Ngalum, Kupel, Lepki, and Murop, Kambon, Una Ukam, Batom, Omkai, and Dapur.

During my journey to Oksibil, the capital of the Star Mountains, I met Elizabeth Singpanki, a 73-year-old woman from the Ngalum tribe. She shared her life story as a woman who continues the traditions of her ancestors.”

Since her husband, Doki Oktemka, passed away in 1984, she has never remarried up to this day. Her daily life revolves around working in the fields, cultivating vegetables and tubers to provide for the food needs of her children. Almost her entire life has been dedicated to her six children: Rudolf Oktemka, Leona Oktemka, Klemens Oktemka, Agustina Oktemka, Amatus Oktemka, and Costan Oktemka.

And as her six children started to grow up, she began to gather orphaned children who had no parents to her home to care for them. She raised and looked after around fifteen children. She supported them all through her work in the fields.

Out of the twenty-one children she once cared for, Costan Oktemka was one of her success stories. He served as the regent of Pegunungan Bintang from 2015 to 2020.”

TRADITION OF GIVING BIRTH TO NGALUM WOMEN

“Women in the Star Mountains now have a better life than women during my time,” she said with a faint smile. “Women nowadays can give birth in a hospital. Back in my day, I had to give birth in a ‘sukam’—a small honeycomb-like structure—deep in the jungle,” she began her story.

In the traditions of the Ngalum tribe and the surrounding tribes in the Central Mountains, it was forbidden for women to give birth in the main house. They had to give birth in a ‘sukam’ in the forest until the baby was born and the umbilical cord was cut. According to their beliefs, men, especially husbands, were not allowed to see their wives’ blood during childbirth.

Mama Elizabeth Singpanki was one of the women who adhered to that tradition.”

Mama struggled on her own, pushing and pulling her baby out of her womb in the cold air. She was only accompanied by the light from a wood fire, which served as both a source of warmth and illumination within the ‘sukam.’ Because Mama had the experience of giving birth to five children before, she no longer needed anyone else to assist in her childbirth. She only carried a ‘nimin,’ a blade, to cut her baby’s umbilical cord.

During the birth of her youngest child, Mama’s eldest sibling, the Ngalum tribe’s leader, passed away. Therefore, she wrapped her still-red baby in leaves and carried the infant from the ‘sukam’ to the ‘bokam iwol’ (traditional house) to participate in the funeral ceremony for the deceased ‘ngolki’ (tribal leader) of the Ngalum tribe, who served as an example for the people of Oksibil.

According to tradition, women and uninitiated children were not allowed to enter the ‘bokam iwol.’ They could only participate outside the ‘bokam iwol,’ even in the case of the passing of a family member who was an ‘ngolki.’ These prohibitions were very strict. They believed that if a baby came into contact with the blood of the deceased and evil spirits, it would disrupt the physical and mental development of the child due to the curse.

However, Mama defied that tradition because she didn’t want to leave her baby alone in the ‘sukam.’ She brought the baby into the ‘bokam iwol.’ Mama’s action angered some members of the community, but she seemed to possess her own strength. She wasn’t afraid of those taboos. In fact, she placed her tiny baby’s body next to her deceased elder sibling with the hope that the positive energy from the spirit of the tribal leader would enter her baby’s body. Mama hoped that one day her youngest son would inherit the leadership spirit of the Ngalum tribe’s leader. And what Mama Elizabeth Singpanki hoped for became a reality. Her youngest son, Costan Oktemka, later became a leader in his own homeland.

Hearing Mama Elizabeth’s story, I can’t help but imagine the struggles she and the mothers of the Central Mountains endured when giving birth in such a manner. In the years from 1970 to 1980, many women and infants in the remote Central Mountains lost their lives due to a lack of knowledge in childbirth care. Everything relied on the law of survival in the vast jungle.

Mama Elizabeth Singpanki was one of the strong and resilient women. She never had a formal education, but she had a far-sighted perspective. She possessed a deep understanding of life and the dignity of a true mother. Mama strongly believed that education, especially for boys, was the path to knowledge and a better life in the future.

In the 1980s, there were indeed government-owned primary schools (inpres schools) in place, but the conditions were very dismal. The schools were often empty because there were no teachers and students attending. This was the way of life for decades, untouched by development and lagging behind in various aspects of life: healthcare, education, the economy, and information.

They lived in ‘honae-honae’ houses lined from the riverbanks toward the mountains. They lived in small, scattered groups, isolated from the outside world, with basic provisions.

The lowlands of the Star Mountains are indeed very difficult to access from the outside. Apart from being surrounded by a series of high mountains, they are also encircled by rivers and swamps. Rivers like Oksibil, Digul, Kawor, Iwur, and Kao are our identities and serve as gateways to other areas. Villages are named after the rivers that flow through them, one of them being Oksibil, the place I visited.

Legend has it that the name Oksibil originated from a pastor named Yan van de Pavert from the Order of Friars Minor (OFM). When he first arrived here, Father Yan asked the local people—using sign language—where he could find water. The locals responded to his question, saying, “Ok sibil balieo,” which means, “The water is nearby.” The word “ok” signifies water, the source of life, flowing through the human settlement. That’s why all the names of the rivers use the word “ok,” such as Okaom, Oksop, Okiwur, and so on.

Throughout the day, the temperature in this area is extremely cold and foggy. The ‘honae’ helps us avoid the risk of freezing to death at night. The temperature gets even colder during a full moon or when the weather is not rainy. When that happens, we warm ourselves in the ‘honae’ with a bonfire.

However, because the ‘honae’ lacks proper air ventilation, the smoke is very bothersome and not good for our health, especially for our respiratory system and eyes. Many residents have died from Acute Respiratory Infections (ARI) due to the smoke from the bonfire. This situation is further exacerbated by the lack of access to healthcare services.

BEGINNING OF ENCOUNTERS WITH THE OUTSIDE WORLD

They began to have contact with the outside world when European missionaries, particularly the Dutch, arrived to spread the mission of Christ’s Gospel.

At that time, botanist L.D. Brongersma conducted an expedition in the Oksibil Valley, bringing along three OFM pastors, namely Jan van de Pavert, Herman Mous, and Gabriel Roes. After their research, all the expedition’s equipment was handed over to the religious advocates. With the remaining supplies from the scientists, the pastors established a government post in Oksibil and began building a Franciscan mission, which involved spreading the message of salvation throughout the Oksibil Valley by constructing churches and elementary schools. The pastors were also assisted by evangelists from Muyu, Paniai, and Keerom.

Mama Elizabeth still remembers, in 1959, when the missionaries first provided services and spread the message of salvation to the people of the Oksibil Valley. At that time, Mama was about 8 years old. That day became a historic day for Mama and the valley’s residents. The people gathered to welcome the missionaries, whom they referred to as “tuan.”

Prior to this, catechists from the Muyu Boven Digoel, Keerom, and Paniai tribes had spread the news of the Dutch missionaries’ arrival to the Ngalum tribe chief and the villagers in their respective villages. They said that the arrivals in Oksibil would be white-skinned “tuans” who came from the south. These “tuans” were considered “magical,” immune to black magic (bitki), and possessed eternal life in the sky. This news was received with joy by some of the Oksibil Valley residents. They hoped that the presence of these magical “tuans” would protect them from death caused by bitki.

The Ngalum tribe’s ancestors had direct knowledge related to nature. Someone was considered knowledgeable if they had specific skills, such as hunting, farming, composing poetry, singing, and dancing. Alternatively, if a person possessed supernatural powers to heal and remove human lives (bit). Bit was an evil spirit that took human lives.

In the past, if a resident fell sick and, after more than three days, passed away, the people of Oksibil immediately believed that the death was caused intentionally by evil individuals using bitki. And because deaths in Oksibil’s community always involved the entire village, if a death was considered unnatural, it often triggered anger and revenge, leading to inter-tribal warfare.

Before the missionaries arrived, inter-tribal warfare was a common occurrence. One such conflict was between the villages of Okipur and Uldopom. These two villages had been at war for months. The cause was the sudden death of a young person from Okipur. The people of Okipur suspected that the people of Uldopom had used supernatural powers to cause it.

One day, the Ngalum tribal chief announced to the feuding villages: “Tomorrow, there will be ‘tuans’ coming to our place. These ‘tuans’ are good people. They bring valuable and fine goods. Axes, machetes, and clothing. These ‘tuans’ are the ones who make sharp axes and machetes. We must stop this war so that the ‘tuans’ won’t leave for another place. So that we can have sharp axes for our gardens. From now on, we must unite. No more enemies. We must all come together. We must live in harmony so that the ‘tuans’ can feel safe in our place. They are safe, and we are safe. So, we must welcome them warmly.”

This announcement turned out to be effective in stopping the war. They reunited.

Their elders had a strong sense of brotherhood and togetherness. Their customs had been passed down through generations, teaching that one clan was one family, one unity that should not be separated. Their ancestors firmly upheld the values of Iwol: a complete life—peace and togetherness with one another, nature, and the Creator (Atangki).

However, because their ancestors also believed in the existence of evil spirits (kaseng) that disrupted human relationships, human connections with Atangki, and human connections with nature, their unity was divided by mutual suspicion, leading to warfare.

After a long wait, the missionaries finally arrived in the Oksibil Valley with religious teachers, mostly from the Boven Digul region. They traveled by boat, sailing up the Digul River, Tanah Merah. They immediately set up temporary missionary tents.

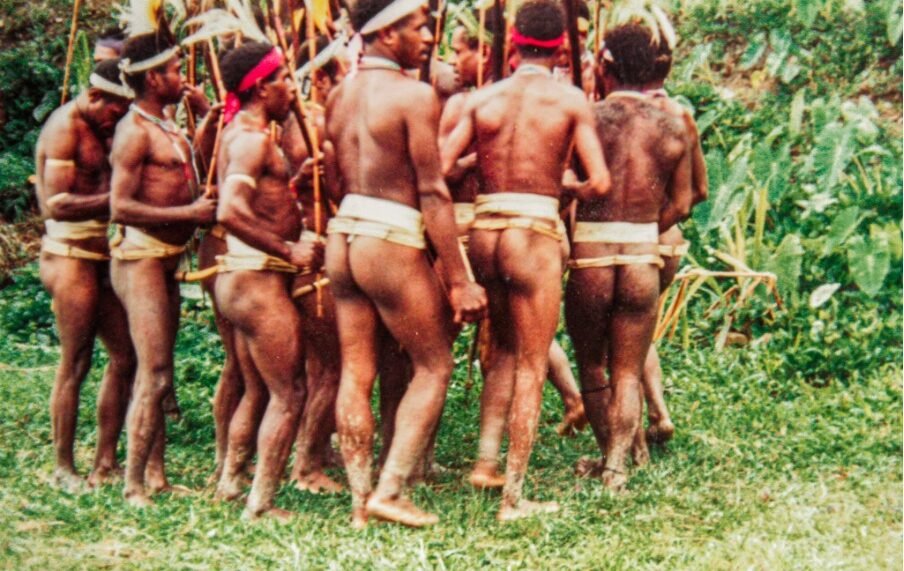

In the morning, the Oksibil Valley community had gathered in front of the tents. The villagers adorned their faces and bodies with red clay. They decorated their hair and heads with bird-of-paradise feathers. Men wore ‘koteka,’ while women wore ‘unom,’ skirts made of straw fibers. They welcomed the ‘tuans’ with dance and poetry. Dancing and reciting poetry were typical traditions of the Ngalum community for welcoming guests.

During this welcoming event, two missionaries from the Netherlands introduced themselves in the Ngalum language. They were Pastor Sibbele Hylkema OFM and Father Maus OFM.

They then distributed various items and food, such as shovels, machetes, matches, mirrors, rice, and salt. This was the first time the Oksibil Valley community saw their own reflections in a mirror, tasted salt, and used matches. These items fascinated them.

“These ‘tuans’ are good. We better follow them so we won’t get hit by arrows or bitki, and we can live a long life with them. We can dress nicely and get a good education,” some of the villagers whispered. “But are they truly magical, immune to bitki’s powers, and have eternal life in the sky?”

This curiosity led them to accept and follow the missionaries’ instructions, even though they didn’t immediately embrace the new teaching: the Gospel. This was because their elders had their own beliefs. A local belief about the cosmology of Aplim Apom.

All the tribes at the foot of the Star Mountains believed that they were descendants of a common ancestor, Atangki (the Hidden God who resides in the eternal life/spiritual realm).

Atangki is a hidden spirit that lives intertwined with the natural world, especially water, forests, mountains, plants, and the rich diversity of living creatures that thrive in this environment.

This view underlies the designation of some sacred places in their region. One of them is Mount Aplim-Apom, located in the central region of the Star Mountains’ indigenous territory, which also serves as the central point for the four dimensions of the mountainous terrain.

In a literal sense, the words ‘aplím’ and ‘apom’ can be interpreted as “house of blood” or “fire.” In a figurative sense, Apom is regarded as a founding father of the nation, and Aplim is seen as the founding mother of the Star Mountains nation. Aplim Apom are the ancestors of the Star Mountains civilization. Additionally, the mountain is considered the highest point of all of Atangki’s creations.

Their elders believed that the world was initially empty, devoid of life. Atangki spoke, and there came mangol (earth), abenongmin (plants), okmin (water), and various aquatic life. Atangki created all kinds of animals. Atangki then placed them in dongkaer (land), ok kaer (water), and damkaer (air).

Then, He created the first man and named him Kaka I Ase (father of all nations). To accompany him, Atangki created a woman and named her Kaka I Onkora (mother of all people). The creation of the first man and woman happened at Aplim Apom, two mountains located in the Star Mountains region. This place was referred to by the Dutch as “strenge bergeete” (Star Mountains) or known as Puncak Mandala. This is where Atangki created the first humans in Star Mountains mythology.

Atangki then placed them in a plain between Aplim and Apom, known as Aplim Bannal Banar Bakon, or more precisely, the area now located in Sibil Seramkatop (Wanbakon region). In this place, the first humans began to chart the course to rule the land of the Star Mountains. In the beliefs of the Ngalum people, all humans on Earth originated from this place.

If someone passed away, their spirit went to kandamil (the origin of each clan) or wokbin–takumbin (a place of abundance). Therefore, our elders believed that our ancestors would protect and watch over us, the living, through an agreement. If someone wanted a good life—security, abundant food, health—they had to take good care of their ancestors’ bodies so that their families, generation after generation, would prosper.”

Their elders believed in all of this. Therefore, when the missionaries arrived, they didn’t immediately change their beliefs, even though they declared their acceptance of the presence of the outsiders they referred to as “tuans.” Most of the inhabitants of the Star Mountains needed time to embrace the new teachings brought by the evangelists. For example, my father held onto his indigenous beliefs until he passed away.

The first step taken by religious leaders in the Oksibil Valley was to gather the community to work together in opening fields with sharp axes, and then distribute salt and matches as rewards.

The Ngalum people, like other mountain tribes, were farmers and gatherers of the bountiful forest produce. We cultivated sweet potatoes (betatas), potatoes, cabbage, carrots, peanuts, as well as cucumbers and chayote. We also collected various fruits from the forest, raised pigs, and hunted in the woods. Our elders already had a strong farming culture, so they were eager to acquire new knowledge in farming.

They then opened schools for the children. They approached each house, inviting children to attend school. Mama was one of the first students to receive lessons in reading, arithmetic, and the teachings of the Christian faith in the Ngalum language.

Mama and the other children then underwent baptism as Catholic faithful. This is where Mama learned the verses of the Gospel about a new creation, the Ten Commandments, birth, death, resurrection, and the power of prayer.

After the children, they opened classes for the mothers. They taught reading and arithmetic, as well as promoting healthy living, especially understanding the female body. Following that, classes were opened for the young men and fathers.

The missionaries didn’t just teach religion, reading, and arithmetic; they also introduced a new way of life, including dressing in clothing that covered the entire body, treating illnesses with specific medicines like black and white ointments, teaching the Indonesian language, and introducing a variety of flavors in cooking to the Ngalum people.

Moreover, after a year of the Missionaries’ presence, they, along with the community, opened a section of the forest for the construction of an airstrip in the Oksibil Valley. This was the first mode of transportation that broke our isolation from the outside world.

Finally, after observing for a long time, their elders accepted and believed that what the “masters” were doing was something good, such as spreading the mission of salvation, providing education, healthcare, and support for the entire population of the Oksibil Valley.

After Oksibil Valley became the first service post, service posts were subsequently established in other valleys in the Bintang Mountains region. As a result, almost 90 percent of the population in the Bintang Mountains now adhere to the Catholic and Protestant religions.

The people of the Oksibil Valley learned many things through their encounters and interactions with the “masters,” pastors, and newcomers. These experiences broadened their perspectives and knowledge, helping them realize the vastness of the universe. This was exactly what Mama Elizabeth always imagined and shared with her children: “Behind those high mountains, there must be diverse and colorful lives. You must go to school so that you can see a broader and better life someday.” .***